WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS

When it comes to optimizing academic performance through neurotherapy, there are two primary goals to consider: 1) removing any deficits (e.g., attention deficits) and 2) enhancing functioning within and between specific brain regions. Neurotherapies have traditionally been used to treat clinical diagnoses and injuries. Often, these diagnoses impede the functioning of many of the skills and behaviors students need to be successful: good memory, quick reactions, focused attention, self-confidence, etc. So, there is a deep history of efficiently using neurotherapies to address any of these skill deficiencies. Researchers have also found success in using these therapies to specifically work with optimizing students’ academic performances.

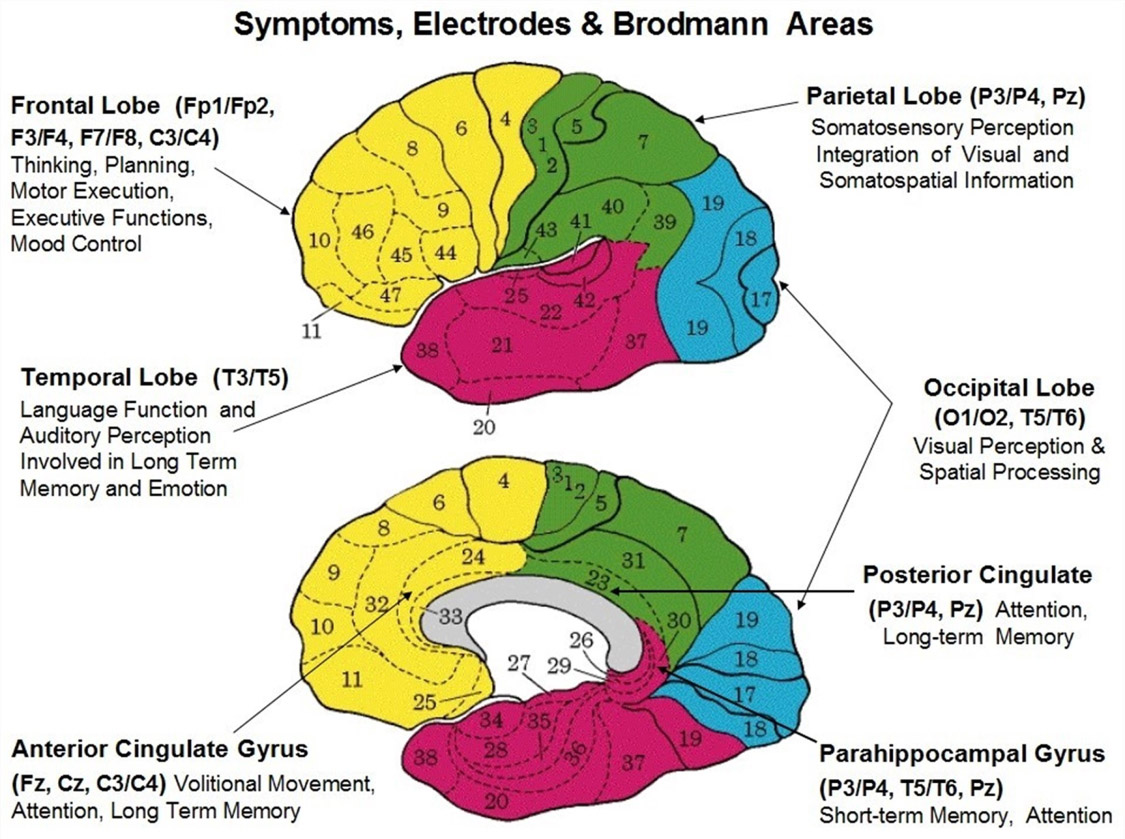

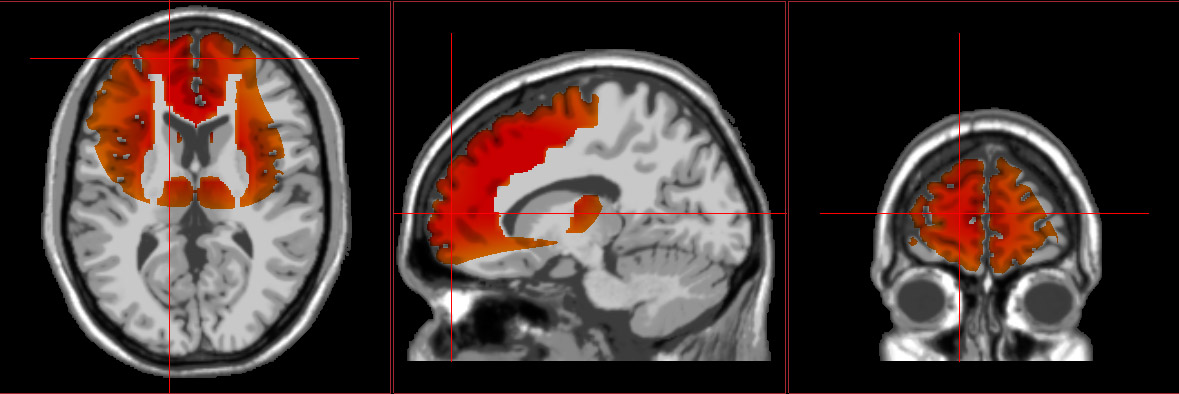

The parietal lobe is responsible for most mathematical comprehension and calculation. It’s important that this region work closely with the frontal lobes to share and receive information. Pasqualotto (2016) was curious whether transcranial random noise stimulation (a form of neurostimulation) was helpful in improving students’ arithmetic skills, but he also wondered about the most effective location site for training (the parietal or the frontal locations). Participants included three groups of students with fairly equal math abilities. One group received tRNS on the parietal lobe, another group on the frontal lobe, and a third group as a placebo. Compared to the placebo, stimulation of the parietal and frontal lobes, resulted in quicker reactions and improved accuracy. It’s believed this is in part due to the treatment benefiting working memory.

Another group of researchers wanted to see if the evidence of neurofeedback benefits on students with learning difficulties was translatable to the non-clinical student population (Fritson, Wadkins, Gerdes, & Hof, 2007). They conducted a study in which 16 college students were randomly assigned to receive a certain neurofeedback protocol focusing on enhancing SMR activity, while minimizing theta and high beta. Participants were assessed on intelligence, attention, memory, emotional regulation, mood, self-efficacy, and impulse control. After only 20 sessions, results showed significant improvements in response control especially.