WHAT THE RESEARCH SAYS

Addiction is as old as the human race. In fact, we’ve even observed addictive behaviors in several other animal species. While origin theories of addiction continue to evolve over time, we now have a better understanding of how our different body systems not only influence its development, but also how addiction influences our brain and body. By addressing the physical roots, we can create a more smooth and sustainable recovery.

One of the first studies on the use of neurofeedback for substance abuse was conducted with combat veterans struggling with comorbid PTSD and alcohol abuse (Peniston et al., 1993). The study utilized an alpha-theta neurofeedback training protocol combined with temperature biofeedback to calm emotional reactivity and make addictive substances less pleasurable to the brain. Results showed a significant decrease in symptoms related to both PTSD and substance abuse in the neurofeedback trainees. These improvements were consistent with significant changes in brainwave activity, which changed in the appropriate direction of training (e.g., theta-alpha crossover pattern). There were also significant improvements in connectivity between occipital, parietal, and frontal brain regions. In a follow-up assessment 26 months later, 80% of the participants reported maintaining complete absence of symptoms and alcohol abuse. This is much better than the average for other treatment interventions, as most studies have found that 40-85% of individuals relapse within the first year following treatment.

Another study by Calloway & Bodenheimer-Davis investigated the use of this same protocol with individuals who had been diagnosed with a substance use disorder. One group received neurofeedback while the comparison group did not. Results showed that 80% of participants from the neurofeedback group were abstinent at 74 and 98 months post-treatment. This not only suggests that neurofeedback can help participants get sober, but also stay sober long-term.

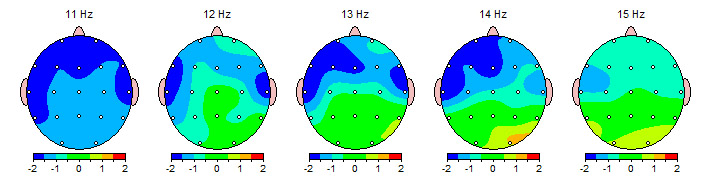

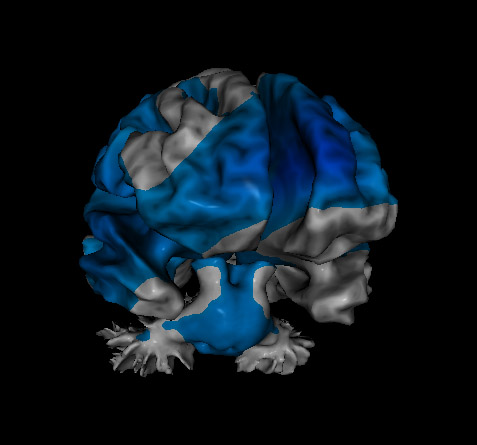

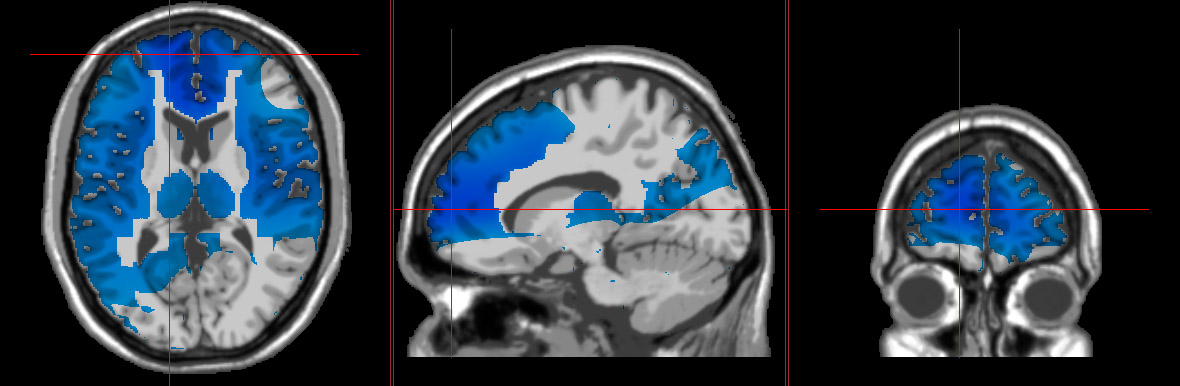

Based on evidence that food addictions are correlated with atypical activity in the brain’s reward system, Leong et al., (2018) questioned whether transcranial pink noise stimulation (a form of neurostimulation) targeting the anterior cingulate cortex would affect cravings and brain activity. Participants in the study were all females dealing with food addiction and obesity. They either received 20 minutes of neurostimulation or a sham treatment every other day for two weeks. Cravings were assessed using the Food Cravings Questionnaire Scale, while brain activity was recorded via EEG. Results showed reduction in food cravings, accompanied by a significant reduction of beta activity in the anterior cingulate cortex for participants who received the neurostimulation. This suggests that this treatment protocol could be an effective tool for managing food addictions.

For more studies on neurotherapy for Addiction, see our Research page.

References:

Calloway, T. G., & Bodenheimer-Davis, E. (2008). Long-term follow-up of a clinical replication of the Peniston Protocol for chemical dependency. Journal of Neurotherapy: Investigations in Neuromodulation, Neurofeedback and Applied Neuroscience, 12(4), 243–259.

Leong, S. L., Ridder, D. de, Vanneste, S., Ross, S., Sutherland, W., & Manning, P. (2017). Effect of transcranial pink noise stimulation of anterior cingulate cortex on food craving. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, 10(2), 351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2017.01.028

Peniston, E. G., Marrinan, D. A., Deming, W. A., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1993). EEG alpha-theta brainwave synchronization in Vietnam theater veterans with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder and alcohol abuse. Advances in Medical Psychotherapy, 6, 37–50.